HON. RODERICK MATHESON

Born: December 1793, in Lochcarron, Ross County (now Ross and Cromarty), Scotland, son of John Matheson and Flora Macrae; m. at Montreal, 5 Nov. 1823, Mary Fraser Robertson who died in 1825, then on 11 Aug. 1830 at Gavilock, Scotland, Annabella Russel by whom he had at least five sons, one of whom, Arthur James*, was treasurer of Ontario, 1905–13;

Born: December 1793, in Lochcarron, Ross County (now Ross and Cromarty), Scotland, son of John Matheson and Flora Macrae; m. at Montreal, 5 Nov. 1823, Mary Fraser Robertson who died in 1825, then on 11 Aug. 1830 at Gavilock, Scotland, Annabella Russel by whom he had at least five sons, one of whom, Arthur James*, was treasurer of Ontario, 1905–13;

Died: Perth, Ont., 13 Jan. 1873.

Roderick Matheson moved to Lower Canada with a brother at the age of 12. He was a sergeant in the Canadian Fencibles when, on 12 Feb. 1812, he was named quartermaster of the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles. He was wounded during the attack on Sackets Harbor, N.Y., on 29 May 1813, and promoted lieutenant on 21 August. He ended the war as the paymaster of the regiment and was placed on the half-pay list in 1816. He was granted land the following year in the military settlement at Perth, around which the rest of his life centred.

Matheson was named returning officer at Perth in 1820. The next year he was gazetted captain in the newly formed 2nd Battalion Carleton militia, and on 18 June 1822 major of the 4th Battalion. These positions were contrary to the rule that militia promotions were to be based on relative seniority in the British army and elicited remonstrances from several half-pay officers senior to Matheson. He was not present at the fray at Perth between a company of the 4th Carleton and the Irish immigrants at the militia muster in April 1824, but he was among the justices of the peace who restored order. He was promoted lieutenant-colonel of the 1st Regiment Renfrew militia in November 1846, and in the next month of the 2nd Lanark. On 14 Sept. 1855 he was made colonel and given command of the 1st military district of Canada West, a post he retained until 1863.

Matheson used his land grant and regular income from half pay wisely. He established a successful general store in Perth, bought land, and was a director in William Morris*’ Tay Navigation Company. On 24 Aug. 1833, he was appointed one of ten commissioners of the court of requests for the 1st division of the Bathurst District, and he was a member of the board of education of Perth. He also took a lively interest in securing internal improvements in the Bathurst District. Sir Charles Metcalfe* put his name forward in 1844 as a possible nominee to the Legislative Council. In February 1847, William Henry Draper again placed Matheson on a list of nominations to Lord Elgin [Bruce*] for a seat in the Legislative Council. He was appointed on 27 May 1847. Matheson sat in the upper chamber as a conservative until 1867 when he was named a senator. He helped in 1855 to defeat a bill supporting an elective Legislative Council by introducing resolutions against the principle.

The first of a series of paralytic strokes in December 1867 disabled Matheson and another stroke on 7 Jan. 1873 caused his death at Perth one week later. Geo. Mainer – Dictionary of Canadian Biography

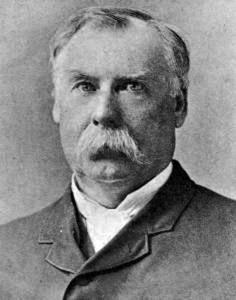

HON. SENATOR PETER McLAREN

Birth: Sep. 22, 1831, Village of Lanark, Lanark County Ontario, Canada

Death: May 23, 1919, Perth, Lanark County Ontario, Canada

Retired lumberman, Perth, Ont.; owner of 100,000 acres of valuable timber lands in Virginia, upon which are also valuable ore mines. Born in Lanark, Ontario, Sept. 22, 1831, son of the late James McLaren formerly of Perth, Scotland, and the late Margaret McLaren, daughter of the late Peter McLaren, of Lochiels Regiment, which engaged in quelling the Irish Rebellion, 1815. Educated: Public Schools. Began to learn the lumber business, 1844, gaining a thorough knowledge of hauling timber, rafting and milling; a partner, Gillies & McLaren, Carlton Place, 1855, which firm bought out the large Gilmour business, consisting of about three hundred square miles of timber on the Mississippi River, Ont., as well as working the Madawaska limits; became Sole Proprietor, 1890; the firm manufactured all kinds of sawn lumber and square timber, the former being for Canadian and United States markets, and the latter for European trade. Summoned to the Senate, 1890. Married Sophia Lees, daughter of the late William Lees, Lanark, Ont., and Granddaughter of the late Col. Playfair, of the old Canadian Parliament, Nov. 22, 1867; has two sons and three daughters. Conservative; Presbyterian. Residence: “Nevis Cottage,” Perth, Ont. David McLaren – Find A Grave

Here is a link to the story of Peter McLaren – Mississippi Lumber Baron by Ron Shaw

http://www.perthhs.org/documents/peter-mclaren-shaw.pdf

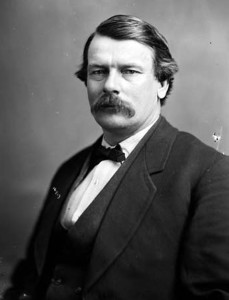

JOHN GRAHAM HAGGART

Born: 14 Nov. 1836 in Perth, Upper Canada, son of John Haggart and Isabella Graham; m. there 26 May 1861 Caroline Douglas, and they had two children

Died: 13 March 1913 in Ottawa and was buried in Perth.

John Haggart Sr arrived in the Canadas in the 1820s from Breadalbane, Scotland, and was engaged as a stonemason on the Welland Canal and as a contractor on the Rideau Canal. He married a native of the Isle of Skye, Scotland, in 1836. In partnership with George Buchanan in 1832, he had acquired a lease to operate Alexander Thom’s grist mill in Perth, on what came to be known as Haggart’s Island in the Tay River. By 1840 he had erected there a cluster of carding, flour, and sawmills and a finely crafted stone house of Regency design.

Educated in the public and grammar schools of Perth, John Graham Haggart was studying law under John Deacon when, after his father’s death in 1855, he took over the family business. For the rest of his life Haggart would be involved in milling. Through various partnerships, he developed the Perth Mills; in 1870–71 the flour mill was rebuilt and in 1886 he converted it to roller-mill technology. By 1896 he had become as well president of the Tay Electric Light Company Limited.

Haggart’s true calling, however, was politics. He sat on the town council, was mayor of Perth in 1861–62, 1863–64, and 1871–72, and tried twice, unsuccessfully, to win election to the Ontario legislature for Lanark South. He withdrew as a coalition candidate before final balloting in a by-election in 1869. Despite his claims to be a Conservative, he ran as a Liberal two years later but he finished second.

The opportunity for federal nomination came in 1872, when the sitting member, Alexander Morris*, resigned to become chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench in Manitoba. Haggart won both the Conservative nomination and the election that year, and he would serve as the mp for Lanark South until his death 41 years later. In the late 1870s he replaced Senator Alexander Campbell* as the leader of eastern Ontario Tories in the House of Commons. Following the appointment of Mackenzie Bowell to the Senate in 1892, he would assume leadership of all Ontario Conservatives in the house. He was to be elected chair of the Liberal-Conservative Union of Ontario in 1896. It was not until 1888 that Haggart was elevated to cabinet, as postmaster general. From 1892 to 1896 he was minister of railways and canals. On the deaths of prime ministers Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* in 1893 and Sir John Sparrow David Thompson* in 1894, Haggart was considered briefly for the national leadership. He may have suffered, however, from innuendo relating to his difficult marriage and his womanizing on Parliament Hill, and from his reputation as an idler and “a Bohemian,” as Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*] viewed him in 1894. (Haggart and his wife may have been living apart since as early as 1871.) He will be best remembered as one of the seven men, the “nest of traitors” Bowell called them, who resigned briefly from Bowell’s cabinet in January 1896. All thought Bowell was inept. One of the leaders of this withdrawal, Haggart earned Bowell’s particular enmity for bluntly declaring that the prime minister, “from day to day, from time to time, like a sick girl hanging on to life, had refused to resign.”

Haggart won local distinction in Perth and, later, national ridicule for his role in promoting the construction of the second Tay Canal. In 1880–82, with the aid of Francis Alexander Hall, mayor of Perth, and Manotick businessman Moss Kent Dickinson*, who sought a better water supply for the Rideau Canal system, Haggart pressed a sceptical Department of Railways and Canals for a new branch canal. It would consist of a cut from Beveridge Bay on Lower Rideau Lake to the Tay River above Port Elmsley and a deepening of that part of the route originally created by the private Tay Navigation Company in 1831–34 between the Rideau Canal and Perth. The new public venture fed on the excitement over proposed mining developments in phosphate, mica, and iron ore. The canal was erected in three stages between 1882 and 1891. The final stage exposed Haggart’s self-interested manipulation of funds in creating a waterway, sarcastically named Haggart’s Ditch, that would be over budget and under utilized. Construction was halted after he was found using unexpended funds from a previous contract to extend the canal to his flour mill in Perth just before the general election of 1891. As minister of railways and canals, Haggart was none the less valued by Thompson. He was credited with improving the financial status of the Intercolonial Railway and with overseeing the completion of the Sault Ste Marie Canal, the last link in the chain of Canadian canals connecting the Great Lakes with the St Lawrence. Following the Conservatives’ defeat in 1896, he became a vigorous critic of Liberal railway policy.

As a young man, Haggart had been active in both sports and the militia. After the Trent affair in 1861 [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*], he raised a company of infantry in Perth and served in it as a captain at least until the Fenian scare of 1870 [see John O’Neill*]. At his death in 1913, after a long illness, he was given a full military funeral by the 42nd (Lanark and Renfrew) Regiment. He had been predeceased by his wife, in 1900, and by their two children: one child died in infancy and their son Duncan A., a champion sculler, succumbed to typhoid fever in 1885 while working in the law office of D’Alton McCarthy*. Haggart left all of his property to his widowed sister, Isabella Maxwell Millar. He had been a Presbyterian in religion. Practical and businesslike as a miller, and tough, able, and unpolished as a politician, he was described by the Toronto Globe as one who played “the game of politics like a sportsman.” Larry Turner – Dictionary of Canadian Biography

WILLIAM MORRIS

Born: 31 Oct. 1786 in Paisley, Scotland, second child of Alexander Morris and Janet Lang; m. 15 Aug. 1823 Elizabeth Cochran of Kirktonfield, parish of Neilston, Scotland, and they had three sons and four daughters.

Born: 31 Oct. 1786 in Paisley, Scotland, second child of Alexander Morris and Janet Lang; m. 15 Aug. 1823 Elizabeth Cochran of Kirktonfield, parish of Neilston, Scotland, and they had three sons and four daughters.

Died: 29 June 1858 in Montreal.

William Morris, champion of the Church of Scotland in the Canadas, was the son of a well-to-do Scottish manufacturer. He was brought up in comfort in Paisley where he attended the local grammar school. In the spring of 1801 the Morris family, encouraged by friends in Upper Canada and armed with a letter of introduction to Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter*, set sail for Canada in search of increased wealth. After some hesitation William’s father ventured his capital on the import-export trade between Montreal and Scotland. But in 1804 and 1805 he suffered severe financial reverses and shortly thereafter retired to a farm near Elizabethtown (Brockville), Upper Canada. There, amid heavy debts, he died in 1809. William, who had returned with the family to Scotland in 1802 and remained there with his mother, sister, and younger brother James* for nearly four years, had come back to Canada in the fall of 1806. With his elder brother Alexander, he set out to repay their late father’s creditors and recoup the family fortunes. Not destitute, yet financially unable to engage in the transatlantic trade as importers or wholesalers, they opened a store in Elizabethtown. They became two more of those small merchants in Upper Canada who served as middlemen between the mercantile houses of Montreal and the Indians, loggers, and settlers peopling the edge of the wilderness.

On the outbreak of the War of 1812 William obtained a commission as ensign in the 1st Leeds Militia. He took part in a number of operations culminating in the battle of Ogdensburg, N.Y., in February 1813 when he was detailed by Lieutenant-Colonel George Richard John Macdonell to lead the successful assault on the old French fort. The following year he resigned from the militia to return to the family business. The war had been an exciting interlude, one which convinced him that Canadians were fundamentally loyal to the crown and capable of defending their country.

The brothers, looking for new commercial opportunities, decided to open a second store in the proposed military settlement at Perth. In 1816 William left Alexander in charge of the store in Brockville and travelled to Perth where hard work, frugality, and a keen eye for business drove him up the ladder of success. It was not long before he was the largest merchant in town, and he was soon deeply involved in local real estate. In partnership with Alexander, then with their younger brother James, and by the late 1830s acting independently, William slowly and persistently expanded his speculation in land into the rest of eastern Upper Canada and then right across the province. Mindful of their father’s problems, the Morris brothers were careful never to overextend themselves or to concentrate too heavily in any one enterprise. William wisely invested his excess capital from his land speculation and store in the new Canadian banking industry. Not all his ventures were to prove successful, however. Efforts to provide for navigation on the Tay River between Perth and the Lower Rideau Lake culminated in 1831 in the incorporation of the Tay Navigation Company, behind which Morris was the leading spirit and chief stockholder. The first Tay Canal was opened in 1834, but the company was plagued by lack of funds, and the canal works ultimately fell into decay.

By the 1820s Morris had become a prominent figure in the Perth area. Commissioned a justice of the peace in 1818, he spearheaded the successful campaign the following year to obtain a seat in the House of Assembly for the Perth region. In the area’s first general election in 1820 he was swept into office. A conscientious constituency man, he held the seat for Carleton and later for Lanark without trouble until his appointment to the Legislative Council in 1836 removed him from elective politics. Morris was named lieutenant-colonel of the newly formed 2nd Regiment of Carleton militia in 1822 and remained active in the militia for more than 20 years. During 1837–38, as senior colonel in Lanark County, he twice called out detachments to suppress rebellion and oppose invasion and on one occasion went in command himself. Successful businessman, militia colonel, and leader of the local conservative forces, William Morris was a man to be both courted and feared.

For more information follow the link below:

J. Bridgman – Dictionary of Canadian Biography

MALCOLM COLIN CAMERON

Born: 12 April 1831 in Perth, Upper Canada; m. 30 May 1855 Jessie H. McLean, and they had eight children.

Died: 26 Sept. 1898 in London, Ont.

Malcolm Colin Cameron was always regarded as the son of Malcolm Cameron, politician and businessman of the union era, who probably adopted him. He attended Knox College in Toronto, intending to join the Presbyterian ministry. However, he later chose to read law (in Renfrew), was called to the bar in 1860, and became a qc in 1876. In 1855 he had moved to Goderich, where he built a lifelong legal, business, and political career. He rose to be senior partner in Cameron, Holt, and Cameron, and invested in at least one salt-works in Huron County. (In 1865 salt had been discovered at Goderich, which quickly became the salt-manufacturing centre of Canada, in part because of its accessibility to cheap lake transport.) Beginning in 1856 he served a 12-year apprenticeship in local government, successively as councillor, reeve, and mayor of Goderich.

Cameron was elected as a Liberal to the House of Commons in 1867 for South Huron, and was re-elected in 1872 and 1874. The last victory was voided in 1875 “because of the acts of over-zealous friends.” He did not contest the subsequent by-election, at which Thomas Greenway* was returned. In 1878 Cameron was again elected for South Huron. Following the notorious electoral redistribution of 1882, he switched to West Huron, which he won that year. Narrowly defeated there in 1887, he was elected four years later only to see the result voided; he lost the 1892 by-election to Secretary of State James Colebrooke Patterson by 25 votes. Cameron took the seat back in a January 1896 by-election and held it at the general election in June. His ten campaigns over nearly 30 years were always fiercely fought and usually settled by narrow margins.

In parliament Cameron, a staunch Liberal, only occasionally showed his severely partisan side. He was most often the principled critic on a bill’s second reading, ready to move or support constructive amendments. His two constant concerns were harbours and salt. From 1867 to 1897 he argued for the development and maintenance of Goderich as a free harbour of refuge (one operated primarily for the shelter of small craft rather than as a commercial port charging fees for docking), as well as the development of nearby Bayfield as a commercial port. Largely because of his effort, the federal government spent more than $600,000 on Goderich harbour. That the work began in 1872 under Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservative government is testimony to Cameron’s effectiveness. He also repeatedly urged the protection of Canadian lake shipping from unfair American competition.

From his first session Cameron called for the protection of Canadian salt against cheaper salt imported from Britain and the United States. He was conscious of the conflict between liberalism and protectionism, but in 1870, citing John Stuart Mill, he defended retaliatory tariffs: “Salt stood in a particular position from the wealth of the manufacturers who had resolved to crush the infant manufacture of Canada.” He called for a “national policy and protection of native industry,” with Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie interjecting “No.” During the 1879 budget debate Cameron strove to get in line with party policy, claiming that “he was opposed to the tariff, though he was at one time a Protectionist himself.” None the less, when the budget moved to the ways and means committee, he asked why the salt industry had been “left out in the cold. . . . Our salt interest alone had received no encouragement, no assistance, and no consideration.” He wrung from Finance Minister Samuel Leonard Tilley a promise to consider ways of helping Canadian salt manufacturers. In 1897 Cameron pressed the newly elected Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier* to impose a tax on American and British salt, but he still maintained that “this is not protection in the ordinary sense of the word, as hon. gentlemen opposite understand it.” On no other issue did his views come so sharply into conflict with those of his party.

The west was the major new interest to emerge during Cameron’s parliamentary career. In 1880–83 he made regular summer trips to Manitoba and the northwest. Macdonald alternately teased and goaded him for his well-known private interest in western lands; in 1885 he accused Cameron of speculating in Métis scrip. In attacks on the government, commencing in 1880, Cameron took particular aim at Indian Affairs (a department under Macdonald from 1878 to 1887). He focused on the waste and corruption that retarded settlement: dominion land guides got settlers lost, land speculation around Regina hindered settlement, the administrative costs of Indian Affairs and the North-West Mounted Police were excessive, and crown land was being sold privately. Aware of agitation in the northwest, he moved a private bill in 1884 and again early in 1885 to provide elected representation for the territories in the commons, but without success. In the 1887 election his charges against Indian Affairs led to a campaign against him, including a government pamphlet to refute his allegations.

Re-elected in 1896 in the midst of debate over federal remedial legislation for Roman Catholic schools in Manitoba, Cameron made only one brief speech, opposing coercion of the province and claiming more could be obtained for the Catholic minority through compromise. The remedial bill he called hypocritical since it was opposed by the Orange lodge yet the government had in the lodge one of the “principal elements” of its strength. Cameron had earlier opposed a federal charter for the lodge and denounced the hanging of Louis Riel* as mere revenge for the death of “Brother” Thomas Scott*.

As prime minister, Laurier found Cameron’s protectionist leanings and his continued, inveterate campaign against the administration of Indian Affairs and the NWMP embarrassing. Still, his interest in the west made him an obvious candidate for the lieutenant governorship of the North-West Territories, into which office he was sworn on 7 June 1898. Less than three months later he took a leave of absence for reasons of health and returned to Ontario. He died at his son-in-law’s house in London on 26 September at the age of 67.

Cameron’s career illustrates the tensions of a Liberal in an era of Conservative dominance. He found it difficult to reconcile tangible personal and local interests with the demands of a party only just coming into being. Perennially in opposition, after the 1896 election he could not adjust to a new role as a member of government. Although a contemporary Goderich journalist, Daniel McGillicuddy, claimed that Cameron had “reduced invective to a science,” his parliamentary career was one of constructive critical opposition. Peter A. Russell – Dictionary of Canadian Biography

REVEREND WILLIAM BELL

Born: 20 May 1780 in Airdrie (Strathclyde), Scotland, eighth and last child of Andrew Bell and Margaret Shaw; m. 13 Oct. 1802 Mary Black in Leith, Scotland, and they had eight sons and one daughter.

Born: 20 May 1780 in Airdrie (Strathclyde), Scotland, eighth and last child of Andrew Bell and Margaret Shaw; m. 13 Oct. 1802 Mary Black in Leith, Scotland, and they had eight sons and one daughter.

Died: 16 Aug. 1857 in Perth, Upper Canada.

William Bell came from a background of agriculture and minor rural trades. His father was a severe, patriarchal Presbyterian and William, thirsting for freedom, ran away from home twice, the second time to London in June 1802. There he worked for a number of carpenters and cabinet-makers before becoming a building contractor in 1805.

Although he had spent only some random months in school, he was a voracious reader and had always longed to be a minister. In 1808, against the wishes of his wife and family, he sold his business and entered the Congregational Church’s Hoxton Academy in London to train for the ministry. He was licensed to preach by the Middlesex Congregational Court on 18 Feb. 1809, but, hoping to become a Presbyterian minister, he returned to Scotland in 1810. While teaching school at Rothesay to support his wife and children, he studied at the Associate Synod of Scotland’s seminary at Selkirk, and, from 1812, attended classes at the University of Glasgow as well. In May 1814 he moved his family to Airdrie and devoted himself full time to finishing his studies. On 28 March 1815 he was licensed to preach by the Associate Presbytery of Glasgow.

Unpopular as a preacher and of a prickly disposition, he was unable to find a congregation and was obliged to work as an itinerant relief preacher. After months of constant travelling he decided in 1816, despite his wife’s protests, to accept the Colonial Office’s proposal of a land grant and a £100 salary to serve as minister to the government-assisted Scottish settlers at Perth, Upper Canada. Bell was ordained by the Associate Presbytery of Edinburgh on 4 March 1817, and a month later sailed with his family for the Canadas.

They arrived at the end of June to find Perth in an uproar, the immigrant families, disbanded soldiers, and half-pay officers having come only the year before. Seeing all around him what he believed to be rampant moral decay and social anarchy, Bell turned his considerable energies to organizing a congregation, teaching school, conducting pastoral visits, and building a church (First Presbyterian). Over the next decade he saw the village stabilize and his congregation quadruple.

In 1817 the Presbyterian church in the Canadas was in a very early stage of development; the four ministers in Lower Canada and the nine in Upper Canada operated without a permanent presbyterial organization. Before leaving Scotland, Bell had been approached by members of the Associate Synod of Scotland asking him to attempt to form a presbytery in the colony that could be allied to their synod. Within a month of his arrival, he and three other ministers, William Smart, William Taylor, and Robert Easton, applied to the Scottish synod for authority to organize a presbytery in Canada. Bell, initially arguing that they should obtain prior approval from Scotland before acting, split with his colleagues when they decided in January 1818 to establish an independent body, the Presbytery of the Canadas. He soon changed his mind, however, and joined them the following July when organizational details were worked out, including, at Bell’s suggestion, acceptance of the principle that the new presbytery recognize “the doctrines, discipline and worship of the Church of Scotland.” The presbytery experienced a number of mutations, ultimately evolving into the United Synod of Upper Canada in 1831. Bell took a keen interest in its proceedings, but his bitter quarrels with most of his colleagues, particularly those of Irish extraction, more often than not hindered progress.

The Church of Scotland forces in the colony were on the rise by the late 1820s and part of his congregation in Perth joined them in 1830, securing the services of the Reverend Thomas C. Wilson, and, in 1832, building St Andrew’s Church. Bell, too, longed for the respectability of membership in the Church of Scotland and had often publicly argued for a union of all Scottish ministers in the Canadas, but he felt it should be done in an organized, official way. He was happy when merger negotiations opened in 1832 between the United Synod of Upper Canada and the Synod of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection with the Church of Scotland. However, disagreement over this question and over a government grant in 1833 shattered the United Synod. Eight members withdrew the following year and, in October 1835, amid much acrimony, Bell also left, joining the Church of Scotland affiliate. Although elected moderator in 1845, he played a minor role in his new synod. On most issues he aligned himself with the more evangelical members; unlike them, however, he did not leave the church as a result of the disruption of 1844, considering the fight to be a solely Scottish affair.

Bell found it difficult to fit into a diversified society, believing as he did that the minister held a unique position in the community and should be recognized as the unquestioned arbiter of all moral standards. His intense sense of divine mission coupled with an irascible disposition and sanctimonious temperament led him into repeated clashes with most of his neighbours and associates. Yet his indefatigable energy and missionary zeal did much to keep the Presbyterian faith alive among the settlers. He established temperance societies, Sunday schools, and Bible classes, and helped found congregations in Beckwith Township, Lanark, Smiths Falls, and Richmond.

He had good reason to be proud of his family. A younger son, the Reverend George Bell, was a student of Alexander Gale and became one of the first alumni of Queen’s College, Kingston, later serving as its registrar and librarian. Another son, Andrew, also joined the ministry and faithfully served a number of congregations before predeceasing his more robust father by some 11 months. William, whose intemperate habits embarrassed his father, had died in 1844 at the age of 38. Shortly before his own death, William Bell ended the long-standing rivalry between the Presbyterians in Perth by bringing about the reunion, in May 1857, of his congregation and that of St Andrew’s. J. Bridgman – Dictionary of Canadian Biographies

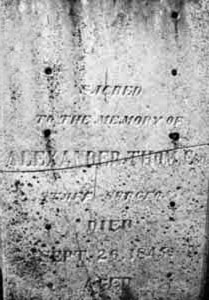

ALEXANDER THOM

Born: 26 Oct. 1775 in Scotland, probably in Aberdeen, son of Alexander Thom, farmer; m. first 5 Dec. 1811 Harriet E. Smythe (d. 1815) in Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada, and they had children; m. secondly Eliza Montague (d. 1820); m. thirdly Betsy Smythe, and they had a son and two daughters.

Died: 26 Sept. 1845 in Perth, Upper Canada.

Alexander Thom graduated from King’s College, Aberdeen, with an ma in 1791. On 25 Sept. 1795 he joined the 88th Foot as regimental mate, a post he assumed in the 35th Foot a year later. He became an assistant surgeon on 9 March 1797 and a surgeon on 30 Aug. 1799. In May 1803 he joined the 41st Foot, then stationed in Lower Canada, and served with it until he became a staff surgeon on 29 July 1813. His status is indicated by the fact that, in October 1812, he was a member of the official funeral cortège for Sir Isaac Brock at Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake). Thom was one of those taken when the Americans captured Fort George in May 1813, and he remained in captivity until August. At that time he received permission from the Reverend John Strachan to use his church at York (Toronto) for a hospital.

Towards the end of the war, the British government sought means to protect the Canadas’ lines of communication against future invasion from the south. The St Lawrence River was patently unsafe, but Montreal and Kingston could be joined by a route along the Ottawa and Rideau rivers if this route could be settled. Thus, a scheme to promote such settlement by reliable British subjects, preferably with military experience, was born. The first community was to be at Perth, and, as it was to be under the protection of the army during its formative years, the British government agreed to provide a surgeon for the settlers. Thom was recommended for this position on 15 Aug. 1815. That December he was apparently responsible for presenting to the provincial government a memorial on behalf of the first group of Scots settlers, who were reluctant to proceed to the Perth settlement because they understood that the land and climate there were unsatisfactory. By July 1816 he was at Perth on half pay. Retiring from this half-pay position on 15 Feb. 1817, he continued as the settlement’s official doctor until military supervision ended in 1822.

Thom lived the remainder of his life at Perth, where he was a force in assuring the survival and growth of the town. In the early years his medical activities were often arduous; in September 1816, when the population was about 1,600, he requested additional medical men and urged that a hospital be built. At about this time he began to establish a business career that soon preoccupied him. He built a sawmill on the Tay River, which produced its first boards in July 1817, and soon after he built a grist-mill; in the opinion of William Bell*, the pioneer Presbyterian minister in Perth, Thom became so involved in these projects that he sometimes neglected his medical duties. In 1819 he was granted land in Perth and in the townships of Bathurst, Drummond, Sherbrooke, and Elmsley. Two years later he joined with other local citizens in petitioning for a market and fair. A magistrate from 1816, he was a member of the court of inquiry appointed by the military superintendent of the settlement, Cockburn, in 1819 that discovered the peculation, of Joseph Daverne, the secretary-storekeeper for the Perth settlement. In 1824, with other magistrates, he faced the difficult task of controlling the “Bally-ghiblin” riots in Ramsay Township.

As Perth grew, Thom’s influence lessened. A tory, he withdrew from the general election of 1824 in favour of fellow tory William Morris but lost to him in 1834. Thom was elected in the Lanark by-election of February 1836 only to lose to Malcolm Cameron and John Ambrose Hume Powell in July. According to William Bell, Thom was a decent man and the only doctor in Perth capable of rising above a concern for financial gain during the cholera epidemic of 1832. When the other medical men declined to form a board of health, Thom announced that he would serve alone, if necessary. The following year he fought a duel with Alexander McMillan “to decide an affair of honor.” Shots were exchanged and, though Thom was slightly wounded, “the matter terminated amicably.” Appointed a district court judge in 1835, he died in Perth ten years later. Charles G. Roland – Dictionary of Canadian Biographies

ALEXANDER MORRIS

Born: 17 March 1826 in Perth, Upper Canada, eldest son of William Morris and Elizabeth Cochran; m. in November 1851 Margaret Cline of Cornwall, Canada West, and they had 11 children.

Died: 28 Oct. 1889 in Toronto, Ont.

Alexander Morris was born to privilege, privilege which he used to expand the fortunes of his family and his country. He spent his childhood in the military settlement of Perth among the mercantile and political élite of which his father was a leading member. William Morris had served in the House of Assembly and the Legislative Council of Upper Canada and was appointed to the Legislative and Executive councils of the Province of Canada. He was active in the interests of Scottish colonists and the Church of Scotland, and in the founding of Queen’s College at Kingston. His son inherited the legacy of a mid-Victorian sense of public duty and family place as well as a network of political friends. Educated initially at Perth Grammar School, Alexander was sent to Scotland in 1841 where he spent two years at Madras College, St Andrews, and at the University of Glasgow. He was employed for the next three years in Montreal by Thorne and Heward, commission merchants, acquiring skills which were to be of use to him throughout his career. In particular, his command of French was aided by a three-month sojourn with a French Canadian family at Belle-Rivière (Mirabel), Canada East.

In 1847 Morris moved to Kingston to study law as an articled clerk, along with Oliver Mowat, under John A. Macdonald. He was admitted into the second year at Queen’s College. He “worked so hard his health gave way,” and in 1848 he left Kingston and returned to Montreal.

At 27 he had published an academic treatise on the railway consolidation acts of Canada, a work of some utility in the pre-confederation decades. Like his father Morris was also active in the affairs of the Church of Scotland. At first mainly interested in missionary and educational work, in 1856 he assisted in beginning and in editing a children’s magazine, the Juvenile Presbyterian. Morris had also been elected a fellow in arts of McGill College in 1854 and in 1857 was elected to the board of governors. Morris was an attractive public figure by the 1860s. A successful lawyer with good family connections and interests in education and his church, he was an able public speaker in English who could also cope in French and whose style in English could encompass the heights and extravagances of the new imperialism of the St Lawrence. Morris had been considering political life for some time and had made inquiries about a suitable riding. In 1861 he was elected as a Liberal-Conservative for Lanark South in Canada West; his father had represented Lanark in the Upper Canadian assembly for more than ten years.

By 1864 Morris had returned with his family to Perth to take up residence in his constituency and to open a law partnership. His business interests, like those of many of his class, were expanding on the eve of confederation. Investments in iron ore, plumbago, and canals led not unnaturally to an interest in railways and the advocacy of a railway from Montreal to Ottawa and thence to Perth and Parry Sound. By 1867 Morris had taken a leading role in founding the Bedford Navigation Company; he and Richard John Cartwright were among the directors. He was also named to the board of the Commercial Bank of Canada in that year.

In the first federal election Morris was re-elected in Lanark South, ensuring, as Macdonald had anticipated, that he would now be able to “begin to play for taking a prominent part in the Conservative ranks.” After some urging, Macdonald appointed Morris to the cabinet as minister of inland revenue on 16 Nov. 1869. Morris’ cabinet position was confirmed by his return by acclamation in Lanark South in the necessary by-election.

Morris’ ten years in parliament were useful if not outstanding. He clearly served his constituents to their satisfaction and provided consistent support to Macdonald. He introduced two liberal reforms, the abolition of public executions and the municipal registration of vital statistics, which found easy acceptance. He gave the impression of being less partisan than many of his colleagues and was thus able to be a conciliator at a crucial time in Canadian political history.

The difficulties of federal politics, medical advice to retire from politics, and financial troubles resulting from a dearth of legal business in Perth, led Morris to leave federal politics in July 1872.

From July to December of 1872 Morris served as the first chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench of Manitoba, a task which would hardly seem suitable for a sick man. In addition, he acted as administrator of Manitoba and the North-West Territories after the departure of Lieutenant Governor Archibald in mid October.

For more information follow the link below:

Jean Friesen – Dictionary of Canadian Biography

THOMAS SCOTT

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Scott was born in Lanark County, Ontario on February 16, 1841. is parents were both from County Antrim and had come to Canada in 1836. He published “The Perth Expositor” from 1861 -1873. He went west with the outbreak of the first Riel Rebellion in 1870 as a member of the Ontario Rifles. During the second Rebellion he organized the 95th Battalion. Scott served as mayor of Winnipeg, Manitoba from 1877 -1878. A strong Conservative, Scott sat in the Manitoba Legislature as the member from Winnipeg from 1878 -1880.

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Scott was born in Lanark County, Ontario on February 16, 1841. is parents were both from County Antrim and had come to Canada in 1836. He published “The Perth Expositor” from 1861 -1873. He went west with the outbreak of the first Riel Rebellion in 1870 as a member of the Ontario Rifles. During the second Rebellion he organized the 95th Battalion. Scott served as mayor of Winnipeg, Manitoba from 1877 -1878. A strong Conservative, Scott sat in the Manitoba Legislature as the member from Winnipeg from 1878 -1880.

He was elected to the Canadian House of Commons as the Conservative member from Selkirk, Manitoba in 1880 and from 1882 – 1887. He served as the Controller of Customs at Winnipeg from 1887 – 1910. Thomas Scott died at Winnipeg on February 12, 1915.

An early pioneer lawyer, judge and politician of London, Ontario, John Wilson was born in Scotland, February 5, 1807, coming first to Perth, Ontario with his family about 1823. In his youth he fought a duel, killing a fellow law student but was acquitted on the charge of murder. After being called to the bar in 1835 he joined a law practice at Niagara and later set up his own practice in London. A reputedly active, robust and popular man who spoke his mind, he served in the militia in 1838, was Warden for the London District from 1842 to 1844 and became Solicitor for the City of London. He was later elected to the Provincial Legislature and achieved Queen’s Counsel in 1856. By 1863 he became a Judge in the Court of Common Pleas. Although he moved to Toronto, he kept his home in Westminster Township and died there on June 3, 1869.

An early pioneer lawyer, judge and politician of London, Ontario, John Wilson was born in Scotland, February 5, 1807, coming first to Perth, Ontario with his family about 1823. In his youth he fought a duel, killing a fellow law student but was acquitted on the charge of murder. After being called to the bar in 1835 he joined a law practice at Niagara and later set up his own practice in London. A reputedly active, robust and popular man who spoke his mind, he served in the militia in 1838, was Warden for the London District from 1842 to 1844 and became Solicitor for the City of London. He was later elected to the Provincial Legislature and achieved Queen’s Counsel in 1856. By 1863 he became a Judge in the Court of Common Pleas. Although he moved to Toronto, he kept his home in Westminster Township and died there on June 3, 1869.

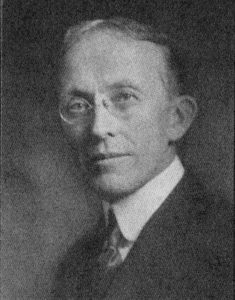

JOHN ALEXANDER STEWART (1867-1922)

John was son of Perth’s famous distiller, Robert, of Dunkfeld, Scotland, was a lawyer, politician and industrialist. He served 2 terms as mayor of Perth, owned McLaren’s distillery and attracted Henry K. Wampole Co. to Perth in 1905, followed by Jergiens. He aquired the Perth Shoe Co. and becam a Director of Frost and Woods in Smiths Falls. He was the Minister of Railways and Canals in Arthur Meighen’s cabinet of 1920-21. His wife Jessie Mabel Henderson (1869-1956) became National President of the IODE and gave Stewart park to the town.

John was son of Perth’s famous distiller, Robert, of Dunkfeld, Scotland, was a lawyer, politician and industrialist. He served 2 terms as mayor of Perth, owned McLaren’s distillery and attracted Henry K. Wampole Co. to Perth in 1905, followed by Jergiens. He aquired the Perth Shoe Co. and becam a Director of Frost and Woods in Smiths Falls. He was the Minister of Railways and Canals in Arthur Meighen’s cabinet of 1920-21. His wife Jessie Mabel Henderson (1869-1956) became National President of the IODE and gave Stewart park to the town.